Foundations of Accountability

Could juries have a role in making governments properly accountable?

Political debate often focuses on how leaders and representatives are chosen. This is undoubtedly very important but, to my mind, the foundation of democratic accountability lies in the public’s ability to dismiss them.

In practice, if millions of people are electing a few hundred representatives, it's impossible for most of the electorate to have much real knowledge of the people they're choosing. So, inevitably, the outcome is primarily determined by the preliminary selection processes. As far as I can see, though, most of us don’t really care exactly who governs us; we just want them to do it well and honestly — and we want to be able to get rid of them relatively easily if they’re incompetent or dishonest.

What makes elections so central in our current system is not that they provide the opportunity to choose a government, but that they provide an opportunity to remove one. However, it’s a highly imperfect opportunity: whatever the interval is between elections it will be too short for the government to give its full attention to the job, and too long for the public to be properly sovereign.

To my mind, therefore, the primary requirement of a mature democratic political system is to allow the people control over the timing of change; and a system which effectively separates the dismissal of a government from the choosing of the next one will in fact allow much more flexibility in how officials and representatives are actually selected.

I believe therefore that, in a mature society, there must be a recognised mechanism whereby the public can spontaneously initiate a change in government at any level.

But … chronic instability?

For most of us, however, a stable society is a high priority and many people worry that, if the public were able to spontaneously dismiss their leaders and representatives, good government would become impossible. It’s a concern which is as old as democracy itself: every extension of popular power has been resisted in the belief that people are collectively incapable of behaving responsibly — but I believe the history of democracy demonstrates just the opposite. In general, people who are given responsibility learn to behave responsibly.

Where democratic societies have behaved perversely – electing demagogues, for example, or demanding damaging reforms – it has generally been fuelled by a sense of powerlessness. When the processes by which leaders and representatives are chosen is flawed, we should not be surprised that the levers of power end up in the hands of unprincipled opportunists who cannot be expected to govern with integrity — and anyone who blames the resulting misgovernment on the public is simply adding insult to injury.

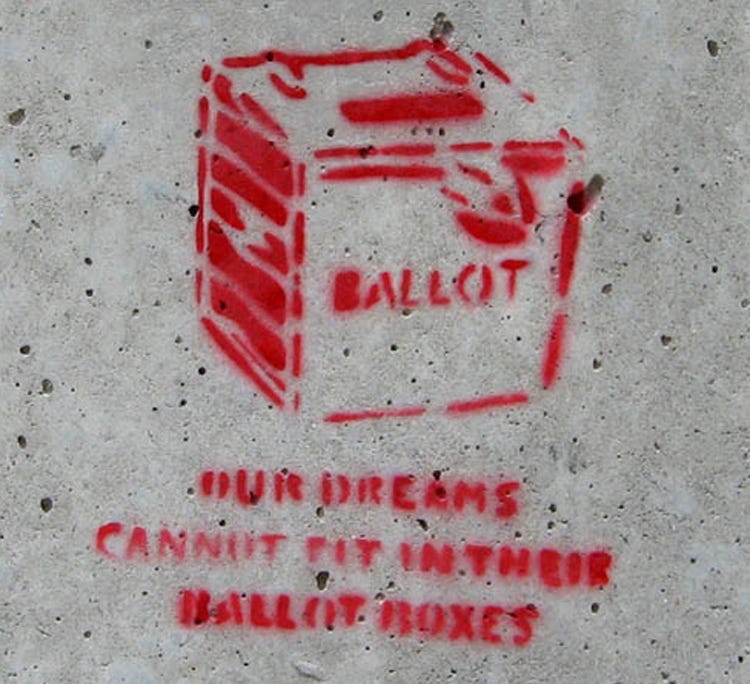

In most democratic countries today, politicians routinely promise far more than they deliver and, in practice, political establishments are widely seen as being more concerned with preserving the power and privilege of their own supporters than with providing good government. The expressions of democratic rage that we’ve seen in recent years have to be understood in that context; all they demonstrate is that a build-up of public frustration will be expressed through whatever outlets are most readily available.

Making it easier for the public to show their dissatisfaction will not make stable government less likely. On the contrary, it will make it more likely because dissatisfaction will be more visible and will have a clear outlet.

That said, I believe one of the functions of a democratic constitution is to give people the government they (collectively) deserve. From that perspective, if the public is indeed so fickle that they demand a new government every other week, I would say that’s what they should get.

In practice, with sensibly designed mechanisms, I would expect government to become more stable than it is at present — because that’s what most members of the public would want. And politicians would find it easier to take a long view; they would know that they could lose power at any time but, once such a process was established, it would no longer be necessary to have fixed terms, so they would be freed from the tyranny of the electoral cycle.

Possible mechanisms

I see two possible mechanisms for spontaneously initiating change, in both of which the institution of the jury is central:

Sovereign Juries (which could also be used for forcing review of unsatisfactory law); and

Jury-moderated petitions (which could also be used for forcing neglected issues onto the political agenda).

The first of these will probably be regarded as a more radical departure from established practice (because it would create a linkage between the political and the legal spheres) whereas the second would simply be an extension of a process that’s already well-established within many political systems. The two are not mutually exclusive and, in my opinion, a mature society would incorporate both of them. The first, in my opinion, would be more appropriate for challenging the monarch or some other holder of high office, whereas the second would be more appropriate for a challenge to an MP or local government representative or leader.

The Sovereign Jury

The jury is sometimes described as the last bastion of our civil liberties but, although many proposals have been put forward for extending its role – whether by selecting members of the House of Lords by lot, or summoning Citizen's Juries – so far it has always been at best a semi-detached part of our constitution.

Currently, the only part the jury system plays in the British system of government is in the judicial sphere, where it is restricted to the role of delivering a verdict on the case in hand. This role is in fact quite separate from what gives it its special status.

As I see it, the essential function of jurors is to act as witnesses to the exercise of power. Through their complicity in a trial the members of a jury confirm the public's acceptance of authority — and in principle they have the power to withhold that confirmation by insisting that the court demonstrate the source of its authority. In my view, this power exists whether it is acknowledged or not because if it happened in today’s world – if a jury demanded that a court demonstrate the validity of its authority – I cannot imagine any court being willing to either ignore it or treat it as contempt.

If that power were acknowledged explicitly, however – if the jury were recognised as holding some sovereignty within the court system – it could (with appropriate safeguards) provide the courts with a mandate of their own which could make them properly independent. It wouldn't have the breadth and depth that Parliament's mandate has, but it would have a topicality which theirs lacks and it would be constantly being renewed each time a new jury is empanelled (I believe it could also offer other benefits but they lie outside the scope of this article).

Although this might be seen as a radical innovation, it could be made manifest within the constitution with no significant disruption. It would also have the benefits of reinforcing the independence of the judiciary, and bringing into the heart of the constitution a treasured institution which has always been a thing apart.

Since the authority of the courts is intimately tied up with their relationship with the Crown, this process could act as the trigger for a motion to replace an unsatisfactory monarch – as I discussed in my previous post, Democratically Accountable Monarchy – or government ministers.

With appropriate safeguards

I am not, of course, suggesting that a single rebellious jury should be sufficient to have someone in high office replaced or even trigger an automatic review of a piece of law; it would be a first step in a process.

The second step, as I envisage it, would involve an official – whose role I’ll be writing more about in a future post – who I think of as the Court Gestor (from a Latin phrase gestor conscientiae curiae, meaning keeper of the conscience of the court). This official would have the power to authorise a hearing in front of a Sovereign Jury1, which might in turn trigger a remedial process of some kind. This might range from the dismissal or prosecution of a minor official at one end to, at the other extreme, a referendum on dismissing the current monarch.

(Alternatively, this second step might end with a call, by the dissenting jurors, for the Court Gestor to be replaced. In this case it would need a quorum of dissatisfied juries – a dozen, say, all within a relatively short period of time – in which case a Sovereign Jury would be convened to hear arguments for and against, which might lead directly to the Court Gestor’s dismissal.)

There are many ways in which this process might work (and plenty of scope for disagreement over the details) but I believe it could significantly strengthen both the accountability of government and the administration of the law.

In the longer term, I would expect the scope of the jury system to be expanded – for example, juries might be empanelled to witness the ratification of Acts of Parliament or, at a lower level, to witness local council decisions – but it would be relatively simple to introduce this reform in outline, simply by formally acknowledging the jury's power to demand proof of authority and establishing basic procedures to be followed if that should happen.

Jury-moderated petitions

The second possible mechanism that I envisage – jury-moderated petitions – would involve two or three steps:

A privately organised petition (to recall an MP or councillor, or to hold a referendum) would need to gather signatures from a certain percentage of eligible voters;

Qualifying petitions would be considered by a jury, i.e. a random selection of voters from the appropriate constituency, who would hear arguments for and against, and decide whether the issue should be put to the wider electorate through a by-election or referendum;

In some circumstances, where the jury approves a petition with reservations, a second jury might be convened to approve details of the vote, or a higher threshold might be set for the petition.

Conclusion

To summarise what I've written above:

the key to democratic accountability is the principle that all positions of authority should be precarious;

the people who occupy them should at all times be subject to dismissal without the public needing to engage in disruptive protests;

an extension of the existing jury system, with appropriate safeguards, could provide an effective mechanism for achieving this in some circumstances;

jury-moderated petitions might be more suitable in other circumstances.

As I said above, there is plenty of scope for disagreement over the details but I hope I’ve made the basic argument clear enough.

A Court Gestor would have the power to authorise a hearing in front of a Sovereign Jury and this would be the only active power they would have.